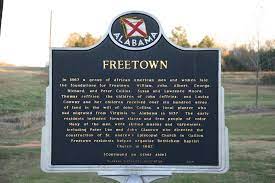

You might only notice the simple country church and accompanying historical marker on Highway 80 in passing, but they represent a truly unique community in the history of the Black Belt.

Freetown, located in Hale County just west of Uniontown, was founded in 1867 by free people of color from the area looking to forge their own community. “Freedom” for African-Americans in the Black Belt in the years following the Civil War was tenuous at best, who found they often weren’t welcome as free people in the towns and cities still dominated by white business and property owners. So towns and informal communities established by freedmen were not uncommon throughout the South in the wake of the Civil War, but few intentional communities of free people of color had the staying power of Freetown.

The founders of the town include John, Albert, George, Richard, and Peter Collins; Susan and Lawerence Moore; Thomas Jeffries; the children of John Jeffries; and Louisa Conway and her children. Many of these families were descendants of or otherwise related to John Collins, a white plantation owner who had come to the Black Belt from Virginia in 1837. Collins first worked as an overseer on the vast Tayloe plantation near Uniontown before becoming a planter and slaveholder himself. Collins had a relationship with a free woman of color, Nellie, who reportedly worked as a housekeeper for him and also became the mother of three of his sons, William, John and Albert. Collins never married, and beyond a certain point there is no remaining historical record of what happened to Nellie. Being the sons of a free woman, though, her children were also legally recognized as free people.

But Collins later purchased another housekeeper in Mobile, an enslaved black woman named Fannie. With her, he fathered three more sons, George, and Richard, and Peter. Unlike his first three children, these three sons were born, and legally remained, slaves. Their story doesn’t end there, however.

When Collins died, he was a wealthy man. He left some of his estate to a white nephew, Joseph Todd Collins. But, while he did not acknowledge them as his children, he also left a large landholding to his sons of mixed race, now free men.

That land would become the foundation for the community of Freetown.

From its original foundation, Freetown grew into a vibrant community where African-Americans could live and participate as full members of a town that was truly their own. The early establishment of a school there would grow into a legacy of education: the historical marker standing there now notes that the women from the Freetown area were recognized as some of the first African-American schoolteachers in the area.

In the years that followed, the town’s population waned as people moved north to seek better lives and more opportunity. But some family members, white and black, still live in the area, and still more retain ties to the area. Freetown reunions have been held every summer at varying locations throughout the country. In 2005, the reunion came home to the Black Belt, and members of John Collins black and white families joined to celebrate the unveiling of the historical marker commemorating the community and its history.